Featured photo: Mourners attending Lt. Richard “Tito” Lannom’s memorial service at Discovery Park of America filled all three floors of the museum.

By Erin Chesnut

Photos by Steve Mantilla

But they never made it.

For Charlotte Lannom, who said goodbye to her husband on the day after Christmas in 1967, the years that followed were some of the darkest in her life. The couple had been married two and a half years when Tito was declared missing in action, and more than 8,000 miles away, Charlotte did what she could to keep courage and hope alive in her life, her classroom and the city of Memphis.

“Those were some growing-up years,” she says. “It was a rollercoaster emotional ride, just not knowing, living in limbo, hanging onto hope. And (asking), ‘What can I do to help?’”

Two and a half years after Tito’s plane was lost, Charlotte joined with other POW/MIA family members in the Memphis area to begin a letter-writing campaign that would ultimately collect half a million letters calling for humane treatment for prisoners of war and an accounting of those missing in action by North Vietnamese officials.

“At that time, I was teaching a sixth-grade class … and those kids would just come in every day with more letters they had collected from neighbors, their churches, Boy Scout or Girl Scout troops, or anywhere they happened to be,” she recalls. “I would have one of those big mail bags in my classroom, and we would fill one up and bring in another one.”

Charlotte and a friend, the local wife of a known POW, and seven others took those letters to Paris in the spring of 1971 and left them at the gates of the North Vietnamese Embassy.

“I hoped to be able to meet with the (North) Vietnamese Embassy officials there and find out the fate of my husband. But, while we were there, my POW-wife friend got a phone call from them, and they said they were willing to meet with her. But they were not willing to meet with me,” she says. “What we figured was true—they were just trying to use (her meeting) as propaganda. … But, for me, that was the stab in the heart that Tito wasn’t being held captive. If so, they would have wanted to try to drive the same kind of propaganda bargain with me. So I left there with nothing but a thread of hope that I clung to for the next two and a half years until the POWs came home. That was when Tito did not. And those were some dark years.”

Almost 600 American POWs who had been captured in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia returned to their families in 1973; more than 2,600 Americans remained unaccounted for, according to the U.S. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

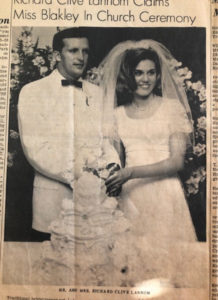

Charlotte and Tito met at the UT Martin Branch and were married in 1965 before relocating to military training sites in Texas, California, Washington and Virginia during the next two years. After Tito left on the USS Enterprise at the end of December 1967, Charlotte returned to Memphis to live with her parents and complete her degree at the University of Memphis (then Memphis State University). Her teaching career motivated her to face each day as it came.

Charlotte encountered many with strong opinions about the unpopular war, but her husband’s courage and commitment to his country gave her the strength.

“I knew Tito was not focused on the politics of the war. For him, it was a commitment to the mission his country had called him to serve. Tito looked fear and death in the face, and honor won out. It was his courage that spilled over into my life of uncertainty. It was his bravery that helped me stand firm,” she says.

Charlotte found her own strength to carry her through the dark times.

“Life is really about choices. In my life, I had the choice then, after all of that happened, I eventually just had to come out of a numbness and a feeling of such sadness and make the choice to live—to make my life count in ways that I hadn’t done before, through my faith in God and through His strength. … I knew that nothing could bring Tito back, but I still had a life to make count.”

Charlotte eventually remarried and is now Charlotte Shaw. She and her husband, Jackie Shaw, have five children and 10 grandchildren, all of whom know about and embrace Tito as a member of the family.

In fall 2017, 49 years after communication with Tito’s plane failed, a remote crash site was discovered on the island of Tra Ban in Vietnam. After a year of DNA testing, an email found its way to Charlotte’s inbox: “It’s been verified. Rick Lannom’s remains have been found.”

“I just happened to pick up my laptop and was scanning over emails, and there it is. It was life-stopping. It was unreal. It was too much to take in at one time,” she says. “It was like going back and hearing it for the very first time. Emotionally, it was overpowering. I’d always dreamed of being able to have his remains back in Union City, his hometown, and be able to have that closure and bring him honor and not just for him to be lost and forgotten. And then, when that happened, it was like he had just been lost, and all those emotions flooded back in.”

Tito’s remains were returned to Union City in March 2019, and the Discovery Park of America hosted a memorial service that filled all three floors of the museum—exactly 51 years and one day after his plane was lost. Charlotte says this service and the associated outpouring of respect from the surrounding community are something she is glad to share with all those still waiting for their loved ones to come home.

“He was just a representative of all those who are still lost out there. That was one of the sweetest things to me to be able to tell him as I stood by his casket, ‘You know, you’re being used in a way that you would have never dreamed,’” she says. “There were so many from these veteran groups, Rolling Thunder and others that were present, and that was powerful and honoring. It was so cold that day, and they would be out there (by the entrance to the park) with flags, standing at attention, and when it would get too cold, there would be another group to take their place.

“Just as they would walk up to the casket and give that slow, honorable salute, you just knew that they were reliving all of their experiences and buddies that didn’t make it back home. … That was a beautiful ceremony that I think gave hope to a lot of people—hope for our country and hope for all that’s good and right that’s still alive and helps define us.”

Since 1973, the remains of more than 1,000 Americans killed in the Vietnam War have been returned to their families, but more than 1,500 Americans remain unaccounted for from that war. Charlotte knows better than most the struggles faced by those waiting for loved ones who might not return—or might not return the same.

“For those families who are on the home front, I know it’s not an easy place to be. Once you’ve been there, you never forget it. … These family members are actually ones that are serving our country, too,” she says. “Family members do, in many ways, go unrecognized. In a way, that family’s positive support and communication from back home to that service member is a very critical weapon, even against the enemy, because it helps to keep that loved one mentally and emotionally fit for service to our country.”

If she could go back, Charlotte has a few words she would tell her younger self—the young woman who still did not know what light could be found at the end of those dark times.

“I would just tell myself, ‘You can be strong because you have faith in your God. He’s going to take you through. And you can just know that God has a purpose, and God has a plan.’ All of this sorrow and all of the hurt, He will use for good, and He will take the darkness and make it light. So, you’re in a dark place right now, but there is light, and that’s what you look for. Find it and shine it,” she says.

“It’s a gift to get up in the morning and know that it’s a glorious new day, and there is hope. We’ve got a reason and a purpose to live.”