By Whitney Heins | Photos By Steven Bridges

Imagine if the state of Tennessee was almost completely devoid of crime. It sounds far-fetched. And, it is. But it isn’t totally impossible. A majority of crimes committed in the state—large and small—stem from the opioid epidemic. And, the opioid problem is worse in East Tennessee than anywhere else in the state.

Knox County ranks third in the state for opioid-related deaths, with 294 dying last year and more than a 186 by the middle of August 2018, according to the county’s Office of the District Attorney General. Neighboring Campbell County ranked third in the nation in 2015 for opioid prescriptions per capita, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

East Tennessee’s locale is the reason behind these staggering numbers. It is part of the Appalachian region, where socioeconomic disparities put people more at risk for addiction, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. It also is situated on the I-40/I-75 corridor, putting it at the end of a drug pipeline that begins in Michigan.

That’s according to UT alumna Charme Allen (Knoxville ’90), who is leading a legal battle against opioid-producing pharmaceutical companies. Allen, district attorney general for the 6th Judicial District in Knox County, is involved in a civil suit launched last fall against three big pharmaceutical companies to try to control the flow of the drugs and to obtain monetary damages for the communities hurt by the epidemic.

The lawsuit is distinctive—state prosecutors aren’t typically involved in civil suits. However, a Tennessee statute called the Drug Dealer Liability Act enables them to sue on behalf of their jurisdictions and municipalities through the representation of a civil law firm.

Allen’s suit is one of a wave that a Nashville law firm is handling. It is the second to be filed, following one in upper East Tennessee. Another one farther west also has been filed, and more of the state’s district attorneys plan to follow suit.

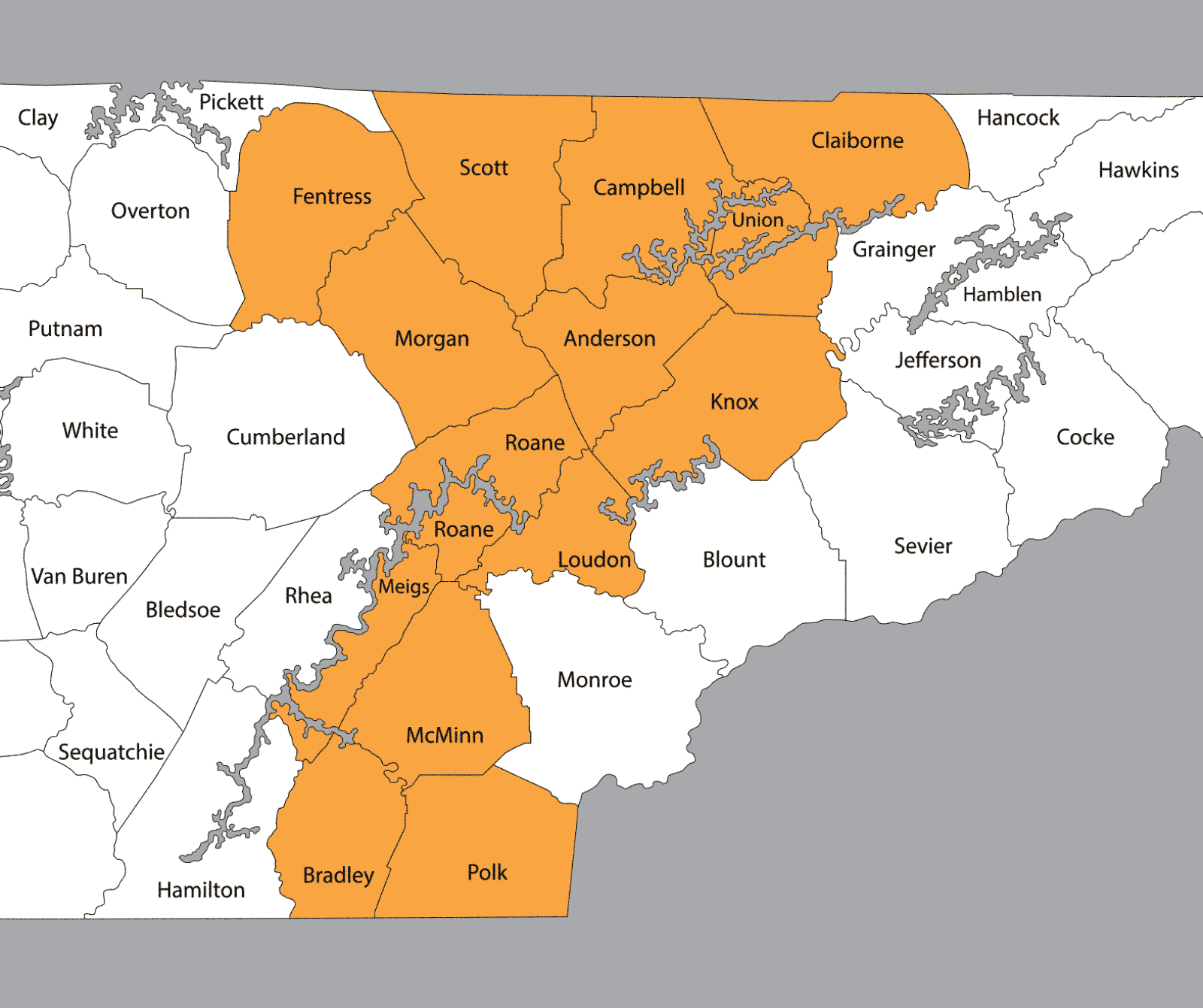

Allen is one of five state prosecutors in the suit—representing Knox, Anderson, Campbell, Claiborne, Fentress, Scott, Union, Loudon, Meigs, Morgan, Bradley, McMinn, Monroe, Polk and Roane counties—filed against the pharmaceutical companies Purdue Pharma, Mallinckrodt and Endo Pharmaceuticals.

Allen and the others are suing under the theory that the drug companies marketed the opioids to physicians as nonaddictive, knowing full well that they were.

“Our theory is that they knew at the time that they were addictive,” Allen says. “We also believe that they knew that they were producing and distributing massive quantities—more than could legally be distributed.”

In fact, in 2016 there were enough prescriptions written for opioids to cover every man, woman and child, and then some, in Tennessee, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Prescriptions lead to the mindset that it’s safe to take the drugs. Then people get addicted and go to so-called “pill mills”—where a doctor, clinic or pharmacy prescribes or dispenses the powerful narcotics inappropriately or for nonmedical reasons—to get more. “People think it is OK. They think, ‘My doctor gave me this or my mama gave me this or my mama takes this, so it must be OK,’” says Allen, who adds this misconception is what makes the epidemic so widespread and difficult to contain—more so than other epidemics such as methamphetamine or cocaine.

Because the problem with these drugs is so different from ones in the past, it requires a different approach than just targeting drug dealers. Hence, the ensuing legal battle with drug makers.

“This started with the pharmaceutical companies….They created them (addicts),” Allen says. “We are doing everything we can possibly think of to combat this problem. We are trying to come up with ideas to address this from a whole different perspective.”

The civil suits are just one tactic in a far-reaching strategy to win the war on opioid abuse, which includes integrative ways to be tougher on dealers and to treat people. An Overdose Death Task Force allows charges against drug dealers for second-degree murder. Drug courts, including Knox County’s, headed by UT law alumnus Knox County General Sessions Judge Chuck Cerny (Knoxville ’86), operate therapeutic programs to rehabilitate addicts. Allen’s office has the novel Vivitrol program that gives select participants monthly injections of Vivitrol, an opioid antagonist that blocks the brain’s ability to feel pleasure from opioids or alcohol.

“Treatment is new for law enforcement. Before, addiction had been oversimplified, but we now know the brain gets rewired and it’s not just a matter of self-control,” Allen says.

The strategy is far-reaching because abuse touches nearly every facet of communities—from streets to jails and hospitals to schools.

The burden is societal and financial. The national economic cost is projected to be around $80 billion per year, including the costs of health care, lost productivity, addiction treatment and criminal justice, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“The problem is so big it is hard to wrap our heads around how much it is overburdening our system,” Allen says.

Jails are overcrowded and have become a sort of mental-health hospital and treatment facility, Allen says. Overburdened hospitals are detoxing people without help from insurance companies, many of which have washed their hands of the problem.

And then, there are the Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) babies born addicted to painkillers because of their mothers’ addictions. NAS babies are on the rise, according to National Institute on Drug Abuse, particularly in Appalachia, and are at risk for long-term problems related to vision, motor development, behavior and cognition—to name a few. They’re also at higher risk for addiction problems down the road. This means they require additional resources and extra attention from specially trained personnel and school counselors, Allen says.

“There are so many people out there trying to stop this. There are just too many problems to handle,” says the district attorney general.

Allen hopes that the outcome of sanctions on the drug companies will help control and monitor the drug flow, while reparations and preventative measures would go a long way in ending the crisis.

Law enforcement and judicial authorities have been successful in recent years in driving down the opioid supply. The number of pill mills and pain clinics is down from 33 to 18 in Knox County. But, behind a silver lining storm clouds loom—the number of overdose deaths is up. In Knox County, 294 died in 2017, up from 224 in 2016 and 170 in 2015, according to the district attorney general’s office. And 2018 is on pace to rival 2017’s deaths.

“We stopped the supply so people had to look somewhere else to get their opioids, and that’s where we had an uptick in heroin. Heroin is cheaper and easier to get once pill mills closed down,” Allen says.

Now much of the heroin and other drugs are cut with fentanyl, a dangerously potent opioid.

“They are cutting everything with fentanyl—cocaine, heroin. And now we’re to the point where they are pressing it into pills. So people think they are getting oxycodone or hydrocodone, and it’s mixed with fentanyl, which is much more potent and why we have the increase in overdoses,” says Allen, before adding law enforcement elsewhere in the state is now seeing it pressed to look like over-the-counter painkillers such as Advil or Aleve.

While it may seem that Allen and her counterparts are playing a game of whack-a-mole, if they can eliminate opioid abuse, then the future for Tennesseans is much brighter with less symptomatic drug and crime issues.

“People who haven’t used drugs before don’t wake up and say to themselves, ‘I think I will try shooting up heroin today.’ They get there somehow. They start with prescriptions,” Allen says.

Photo by Patrick Murphy-Racey

The district attorney general can’t speculate as to how long the civil suit will take, but it is expected to be years.

She’s optimistic they will succeed. Already, they’ve progressed faster than expected (they’re already in the discovery phase) and cleared one major hurdle when the drug makers’ efforts to move the lawsuits out of Tennessee courts into the federal judicial system failed.

Allen hopes that the outcome of sanctions on the drug companies will help control and monitor the drug flow, while reparations and preventative measures would go a long way in ending the crisis.

“We’ve lost an entire generation to this,” Allen says. “But, once we stop the overprescribing and the misconception that they’re safe, then we can educate the next generation coming up… and I think we will see a significant decrease in drug use.”

Allen likens it to seat belts. Years ago, people thought seatbelts were pointless and refused to wear them. But, after a campaign, now most everybody does.

“Like the seat-belt campaign, it is just going to take time,” she said.