By Susan Barnes

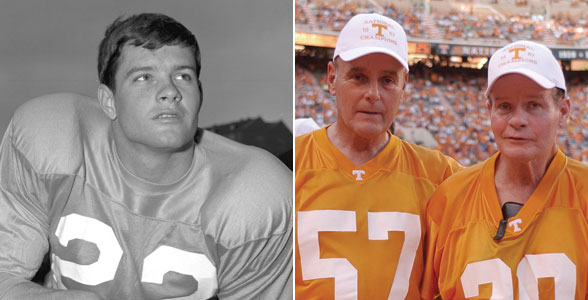

This could possibly be the saddest story you ever read, but it isn’t. Far from it. It’s a story of courage, faith, and friendship that gives a whole new meaning to the phrase “a host of Volunteers.” It begins in 1971. Walter Chadwick, hero of the 1967 Tennessee / Alabama football game who wobbled the game-winning touchdown pass left-handed to tight end Ken DeLong, had just started a promising high-school coaching career in Smyrna, Georgia, near his hometown of Decatur.

That all ended after only 2 weeks when a Wells Fargo truck crossed the center line and smashed head-on into Chadwick’s VW Beetle as he made deliveries for his mother’s gift shop. He was in intensive care for 15 days, in a coma for 3-1/2 months. Many people thought, and still think, he died. “They gave me the last rites,” Chadwick is fond of saying, “but I fooled ’em!”

Instead, he was severely, irreparably brain damaged. He spent 2 years in rehabilitation at Warm Springs. His marriage crumbled, and he lost contact with his two young sons.

Life looked bleak for the most dazzling of the four football-playing Chadwick brothers. All were Decatur legends–Dennis was a standout wide receiver with the Vols when the accident happened. Don and Alan played for Decatur, and Alan still coaches championship teams at Atlanta’s Marist School.

But Walter Chadwick was the star of the show. From 1965 through 1967, he played tailback and ran back kicks at Tennessee. He scored 16 touchdowns–11 in one season–and rushed for 1,306 career yards. His name is in the Volunteer record books as the leading rusher, kick-returner, and scorer during his career. He led the Vols to three post-Âseason bowl games and both SEC and national championships in 1967.

Drafted in 1968 by the Green Bay Packers, he tried out with the Atlanta Falcons, then played a year for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers in the Canadian Football League. “Lost every game,” he chuckles at the memory of his professional football career.

And this is where the sad part begins to end. It may appear that Walter Chadwick lost everything on that April afternoon almost 37 years ago, but he kept his sense of humor, his faith, and his memories of the game he loved to play.

His teammates never forgot him. Former Vol offensive tackle Elliott Gammage (’65 through ’67) visited almost every day while Chadwick was hospitalized. When the responsibility of caring for a severely disabled brother began to wear on the Chadwick family, Gammage became a mainstay in Chadwick’s life.

A native of Cedartown, Georgia, Gammage watched out for Chadwick, taking him to doctor visits and therapy sessions, making sure he was getting to work, helping keep up the small townhouse Chadwick owns in Decatur. When ex-Vols passed through town, Gammage arranged for lunches with Chadwick.

But when Gammage moved back to Tennessee, Chadwick’s fortunes took a turn for the worse. He had worked for a printing company for 15 years, cleaning presses, but the company closed. He did custodial work at North Dekalb Mall and Georgia Tech. With limited speech, concentration, and mobility, he couldn’t find or hold a meaningful job.

That’s when Steve Kiner, All American linebacker at Tennessee from 1967 through 1969, 9-year NFL veteran, and member of the College Football Hall of Fame, came back into his life. “I took him to lunch, and he seemed pretty happy,” Kiner said.

Then Chadwick was fired from the only job he could find, bagging groceries at Publix. He had finished off a can of beer he was returning to the storeroom after it accidentally opened during checkout, a violation of company policy. Publix wouldn’t budge. Even Kiner, a notorious tough guy on and off the field during his playing days, couldn’t get Publix to give the guy a break.

It became apparent to Kiner that Chadwick needed help–a lot of it. His townhouse was falling down, he wasn’t doing his physical therapy, and he needed a job with some dignity. “His rehab group was doing nothing for him,” Kiner said. And Kiner should know. With master’s degrees in clinical psychology and counseling, he has helped plenty of people like Chadwick back onto the path to a productive life. Kiner contacted Briggs and Associates, an Atlanta company that helps traumatic brain-injured and other disabled adults to learn work skills and find “supported employment.”

Kiner became Chadwick’s chief advocate. He went to his bosses at Emory Healthcare, where he manages emergency psychiatric services, to see if Emory could find a job for Chadwick. The director of the Emory brain institute seemed interested, but then he left. “I was running up against human resources at every turn,” Kiner said, but Pat Gausch, the nursing director at Emory’s Center for Rehabilitation Medicine, knew Chadwick could help her patients get better. Kiner’s new boss, Al Blackwelder, finally made it happen.

After 2 years of cutting through red tape and resistance, Kiner helped Chadwick deposit his first Emory paycheck in July 2007. But Kiner couldn’t fix all of Chadwick’s problems. There was the disintegrating townhouse, and Kiner knew from his counseling background that Chadwick needed friends. He went to Diane Prindle, Chadwick’s case manager at Briggs, to ask if she knew anyone on the UT Atlanta alumni board who might help.

Enter Ellen Peters Morrison, who was about to retire from Briggs, and Marilyn Elrod, who was taking a year off from her job as an IT project manager. Both were on campus when Chadwick was starring at Neyland Stadium, and they are still huge Vol fans. Both needed something worthwhile to keep themselves busy. Chadwick was it.

Morrison started a person-centered (and Tennessee-led) planning group at Briggs to support Chadwick. The original members, in addition to Elrod, were Jim Lawson, Frank Weldon, and Morrison’s husband, Philip. Elrod’s sister Bobbie of Manchester, Tennessee, got involved when she came to Decatur to help clean Chadwick’s townhouse–he has a habit of collecting “treasures” on neighborhood trash-pickup day–and the circle began to grow.

“I added some people who were not as old as we are,” Morrison said, “but who were just as committed to Walter.” Malinda Sharp, a Knoxville interior decorator, wanted to help and recruited AOPi sorority sister Trish Sheffield to serve as the contractor on the project. Though not UT alumni, Chadwick’s neighbors Stacy and Kathryn Burnette have joined in.

Morrison, Elrod, and Kiner make sure Chadwick gets to many Volunteer home games (Chadwick says the Volunteer offensive line doesn’t get off the ball fast enough), and Stacy Burnette often takes him to games at Decatur High. “We always have to build in time for the Walter ‘receiving line,'” Burnette says of their dinner and game trips. Decatur fans still remember his on-field heroics.

Chadwick attended the 40th reunion of the Vols’ 1967 national championship team last September and beamed when his game-winning touchdown pass against Alabama was shown on the Jumbotron. Teammate Dick Williams took off Chadwick’s hat and waved it for him to the cheering crowd. “Coach [Doug] Dickey thanked us for all we’re doing,” Elrod said. “But working with Walter helps us more than it helps him. It’s enriched our lives.”

Marilyn says Chadwick was concerned that Dickey, his old UT coach, might think his hair was too long, and he insisted on getting it cut before attending the game. Teammate Bill Young took him to the barber. On the Vol Walk, Chadwick, the top tailback of 1967, got a hug from Arian Foster, the top tailback of 2007. Chadwick and Kiner swapped stories with legendary assistant coach P. W. Underwood. Some were even true.

On the way back to Atlanta, Chadwick found a Patsy Cline CD in Elrod’s car and sang with it all the way home. On another trip, he had quoted scripture to her.

“Walter’s life has turned around a hundred-eighty degrees in the last two years,” Kiner said. Chadwick is a revered figure in Decatur, where he rides his bike to the nearby MARTA station to catch the Emory shuttle for work three days a week. He wants to work five.

If you ask Chadwick what he does at Emory, he’ll tell you, “I encourage people”–people just like himself, who have every reason to lose hope. Kiner tells of a severely brain-injured patient who turned his face to the wall, wouldn’t get out of bed, wouldn’t eat. A half-hour with Chadwick, and the man was in the cafeteria, laughing and talking. Chadwick never quit, and he won’t let other people give up.

Chadwick greets patients with a cheerful “Hey, Slick!” and gets a smile in return. He wears custom-made orange scrubs to work sporting a power-T logo, except on the days he wears his “purple people-eater” outfit.

His best days are when the drug reps bring in pizza for lunch. Or when his gang of friends take him to Maddy’s, a popular Decatur restaurant, for ribs and a beer. There he holds court, showing off the championship ring with the Big Orange stone he always wears.

Elrod has taken him to Knoxville to see his younger son, John, left a quadriplegic from a car accident 10 years ago. He keeps in contact by e-mail with his older son, March, an architect in New York City. March recently visited his dad.

Elrod and Morrison also take him regularly to the nursing home where his 91-year-old mother lives. She suffers from advanced dementia. “They adore each other,” Ellen says of mother and son. “She lights up when he comes in the room.”

The townhouse remodeling project is going well, partly financed by generous friends and Vol fans. However, Chadwick has had to dip into the small trust fund that supports him to pay for the major work. Two UT alumni who work for Home Depot have arranged to donate a refrigerator. Former Vol coach Bill Battle is helping, as is the Atlanta alumni chapter board.

Elrod was working on a project in Washington, D.C., last fall, and wasn’t as available as she once was, which made it clear that the “Walter Team” needs to expand. With 11,000 Tennessee alumni living in the Atlanta area, the recruiting potential is enormous. For information on how to help Chadwick, and to get on the e-mail list of Friends of Walter, contact Morrison at pjmorrison@aol.com.

“Walter will have a job at Emory as long as I’m alive,” Kiner said.

According to Elrod, “he almost needs someone full time” to look after him. One person can’t do it alone. But Walter Chadwick, whose life was almost destroyed in April 1971, is enjoying himself. He may have lost family, many of his physical and mental abilities, and his future, but his sense of humor and his love for the game of football are intact.

He remembers that his dear friend, Steve Kiner the All-American linebacker, used to stand him up in goal-line practices. “Stand you up?” Kiner counters. “I made you see stars!” And Walter Chadwick, football star and star of the Emory Healthcare rehab team, throws back his head and laughs. Life, for Chadwick and for the Volunteers who love him, is good.